Chapter 11

Decentralized & Open Finance

The promise of cryptocurrencies to create a fully fledged parallel financial system came much closer to reality with emergence of the DeFi space that started to shape up in late 2017. By this time, a bunch of different protocols had been proposed to form up new financial primitives in a completely decentralized and open-sourced fashion. Without any doubts, this brings significant benefits compared to the traditional financial system which tends to get into troubles once distrust between the institutions spreads, as seen in 2008. Trust minimization is the key concept here. Making all the crucial components such as the source codes, business logic and cash flows transparent represents a significant paradigm change when it comes to finance.

The early years of this space showed that DeFi has been actually more open than decentralized, and thus Open Finance would be more fitting overarching term. Nonetheless, “Decentralized Finance” or “DeFi” have been widely established and are used commonly by academics, journalists as well as the crypto folks in general. If we accept that the term does not necessarily describe the current state of this space, but rather its end goal, it becomes less irritating. Similarly as with any cryptocurrency network, various degrees of decentralization exist in DeFi too. Even though the vast majority of the protocols live on the Ethereum network, and thus are likewise decentralized when it comes the infrastructure. However, decentralization in DeFi projects entails more dimensions, namely: governance, oracles, and liquidity. We covered governance and oracles in the past chapters. Yet, in the following paragraphs in addition to decentralization of liquidity we explore the nuances in respect to governance aspects in DeFi a little further.

Governance

In the beginning, most of the projects are, naturally, rather centralized as the protocol development is spearheaded by the narrow group of developers. Even though many of these protocols operate as an orchester of different smart contracts interacting with each other, these smart contracts often are managed to some extent by admin keys. These keys are sometimes even owned by a single person, more often though by a group of people using multisig. Having administrators of a smart contract certainly has its trade offs. They can fix bugs or freeze the contracts in case of emergency. On the other hand, such a concentration of accountability may possibly have negative implications in terms of censorability of the contracts, and likely legal implications too. A gradual shift towards administration-less operation is the best practice when it comes to the lifecycle of smart contract applications.

There are, however, instances of smart contracts where this is not entirely possible as functionality of an application depends on a set of dynamic parameters that need to be adjusted regularly. This is the case with many DeFi apps too.A plethora of DeFi projects decided to distribute decision-making over different protocol parameters to a wider community through introduction of governance tokens. This trend has been accelerated since distribution of the COMP token to the users of the Compound protocol. Interestingly, this move came almost two years after the protocol has been in operation without any native token.Suddenly, the protocol users borrowing and lending their assets started to receive new governance tokens. As these tokens rapidly grew in value, their distribution effectively subsidized the protocol utilization. This caused a massive inflow of users and capital. Other projects followed the suite and applied similar practice of incentivizing protocol usage that became known as yield farming. Such a practice was pioneered by Synthetix and caused the exponential growth of the whole DeFi space in a very short time that indeed resembles the ICO bubble in 2017. On one hand, yield farming had multiple benefits including a strong marketing effect, increased brand awareness, influx of liquidity, and rather fair token distribution. Moreover, it also eased the pain of token distribution from a regulatory standpoint. On the other hand, it introduced somewhat perverse incentives with situations where profit seekers borrowed Dai to lend more Dai on a different protocol, to maximize their yields, just to dump it thereafter.

Distribution of governance tokens, and thus voting rights to protocol users reminds co-ops. Co-ops are corporations in which shares are sold to users, creators, or customers of the company. This idea dating back to the 1700s has not been widely deployed mainly because it is operationally inefficient as coordination of large numbers of shareholders is difficult. Co-ops tend to be outcompeted by leaner companies. But in the blockchain realm, the operational efficiency of this concept may be radically improved due to automation on top of the decentralized substrate. Therefore, DeFi projects make an interesting economical experiment in their attempt to apply decentralization to their governance mechanism.

Liquidity

Algorithmic-based liquidity enabled by smart contract liquidity pools is one of the most impactful innovations within the DeFi space. The whole cryptocurrency space has suffered from low liquidity since its inception. As liquidity is essential for the growth of the financial markets as well as price discovery, the lack of thereof hindered expansion of many projects. While crypto whales have been providing liquidity for some projects for some time, having a few large players instead of central banks does not represent much of a paradigm shift compared to traditional finance.One of the first protocols to address this issue was Bancor that stormed the stage with its massive $150 million ICO in 2017. However, not long after it lost ground to another raising star that offered a more elegant solution without any token — Uniswap. Uniswap has managed also to become the most used DeFi apps by mid 2020 as the only protocol with over 100 000 users over time of its existence.Smart contract-based decentralized liquidity provisioning appeared as a brand new concept. With its success the competition has been getting more fierce too as Kyber, Balancer, Curve, BlackHoleSwap, and other protocols entered the market. More scalable and private alternative offered by StarkDEX could even bring the concept of “Dark Pools” (private exchanges for trading securities by large institutions) as we know it from legacy institutions such as Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley.

It is rather disputable to draw a line what in the cryptocurrency space does and does not belong to DeFi applications, but the term is most commonly used for financial smart contract applications, and not cryptocurrencies per sei. In the following paragraphs we will cover the most important use cases and protocols within the space of decentralized finance.

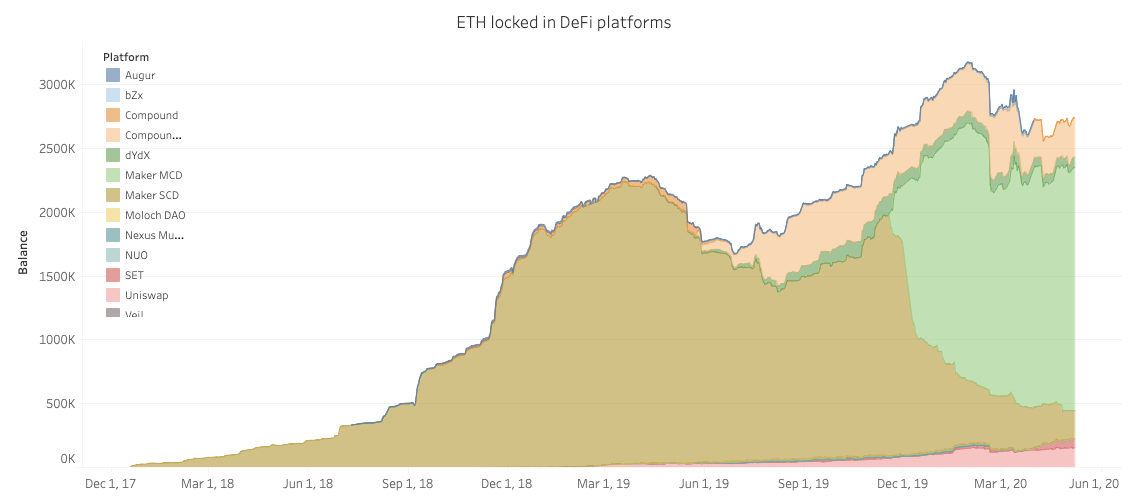

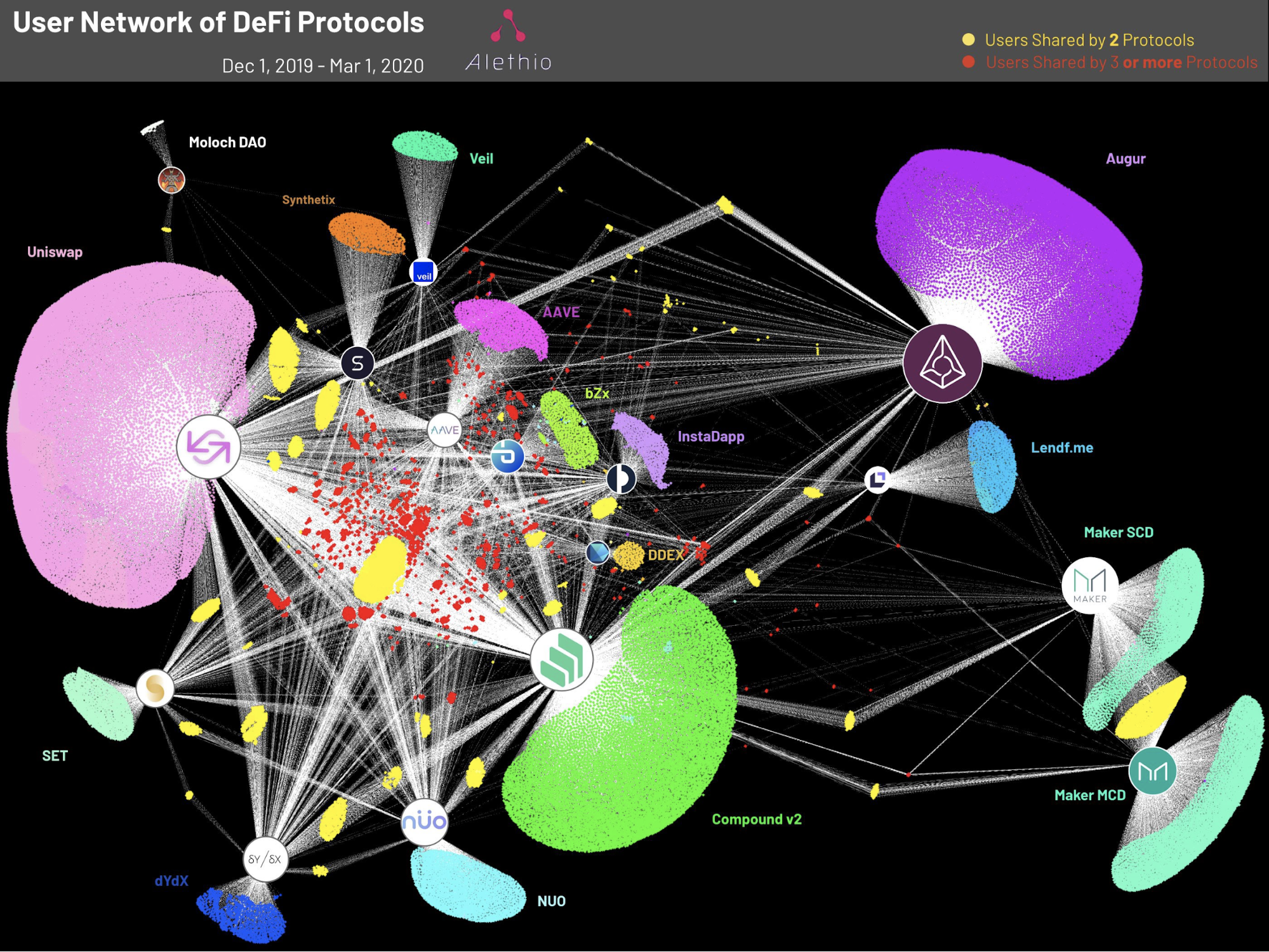

Source: Alethio: 2018 - 2020

Decentralized Exchanges

One of the earliest and most popular concepts within DeFi are decentralized exchanges, or DEXs. They have been the flagship products of the space for obvious reason, and that is trading being the most popular activity for crypto assets. Initially, all cryptocurrencies had been traded on centralized exchanges such as Mt.Gox, Cryptopia, Bitfinex or Binance. While these exchanges, and the companies behind them, offer a smooth experience for their customers they do imply certain risk for users’ deposits. The more dense concentration of funds the more attractive honeypots for the hackers. There are, sadly, too many historical references to prove this point. Naturally, centralized exchanges are subjected to enforcement of strict rules when it comes to reporting, KYC, and AML policies. Decentralized non-custodial exchanges have been, therefore, one of the most demanded services by cryptocurrency afficionados, as they reduce risks of hacks and reporting duties.

Some of the earliest decentralized exchanges emerged outside of the space we today call DeFi. LocalsBitcoins.com was one of the first P2P exchanges that allowed users to trade bitcoins on its marketplace in a decentralized fashion. It was founded in 2012 and based in Finland. Unfortunately, the company and its website was subject of multiple hacks and bans too. In 2014, a team around cryptocurrency named NXT announced their intention to build one of the first DEXs. It was named NXT Asset Exchange and it eventually launched a few months later. All the assets listed on the exchange were traded only against the NXT digital currency, and direct asset to asset trading was not possible. The exchange did not gain many users but it gave us a glimpse of what is to come for this industry. Around the same time, a similar DEX was launched by Counterparty. As all trading orders were escrowed in the Bitcoin blockchain, confirmation of these transactions took quite some time which was not acceptable for most traders. The main problem of the first generation of DEXs was that they were currency or chain dependent which curtailed their disruptive potential. Bisq, previously known as Bitsquare, has been attempting to provide a more elegant alternative through its desktop applications that emerged around 2016.Despite quite low volumes of both of these exchange options, they have provided reasonable fiat on-ramps for many users. Like LocalBitcoins, it utilized hash-time locked contracts (HTLC) that allow for atomic swaps, and is still in operation in 2020.

Many cryptocurrency projects, such as PIVX, Waves, Stellar or Decred, have been working on their own decentralized exchanges that would ease exchanging their native tokens for bitcoins. However, DEXs really kicked off only with advancements within the Ethereum ecosystem.EtherDelta has spearheaded the efforts to bring DEXs to the mainstream in 2016. It was the first exchange offering non-custodial trading that got some major traction within the space. This feature compensated for low general usability as at the time it was the only exchange of its kind. Unintuitive user experience, however, provided opportunities for new players to come. EtherDelta’s hack spurred the debate on degrees of decentralization in regards of exchanges. Non-custodial exchange of tokens was crucial, but order broadcasting and matching were also too important functions to be centralized. Centralized order books are prone to front running, and thus are a single point of failure.Before long, EtherDelta was dethroned by the new kid on the block - IDEX. IDEX came with much more friendly UX and hybrid architecture that combined Ethereum-based smart contracts storing assets and executing trade settlement with centralized trading engine. This way IDEX managed to offer semi-decentralized solution with both high security and throughput. This combination made IDEX for some time the most utilized smart contract in the space. In 2019, IDEX announced their plan to further decentralize various aspects of their exchange by introduction of multi-tier node system. IDEX pivoted the era of decentralized exchanges based on smart contracts and hybrid architecture as we know it today.By 2020, there are dozens of projects deploying different scaling techniques to create decentralized exchange protocols. Even though IDEX has lost its ground to other protocols it still maintains relatively decent trading volumes. The world of DEXs has become much more complex, and many projects entail a unique combination of features that sets them apart from the rest of the protocols by being focused on niche trades.OasisDEX has a completely on-chain order book, built by MakerDAO, to ensure liquidity for Dai and MKR. Interestingly enough, despite of this niche orientation it is one of the biggest DEXs in Ethereum in terms of volume. Other prominent exchanges that have on-chain order book include Kyber Network or exchanges using automated market makers (AMM) like Uniswap or Bancor. On the other hand, there are projects such as 0X and Airswap that utilize off-chain relays with on-chain settlement.

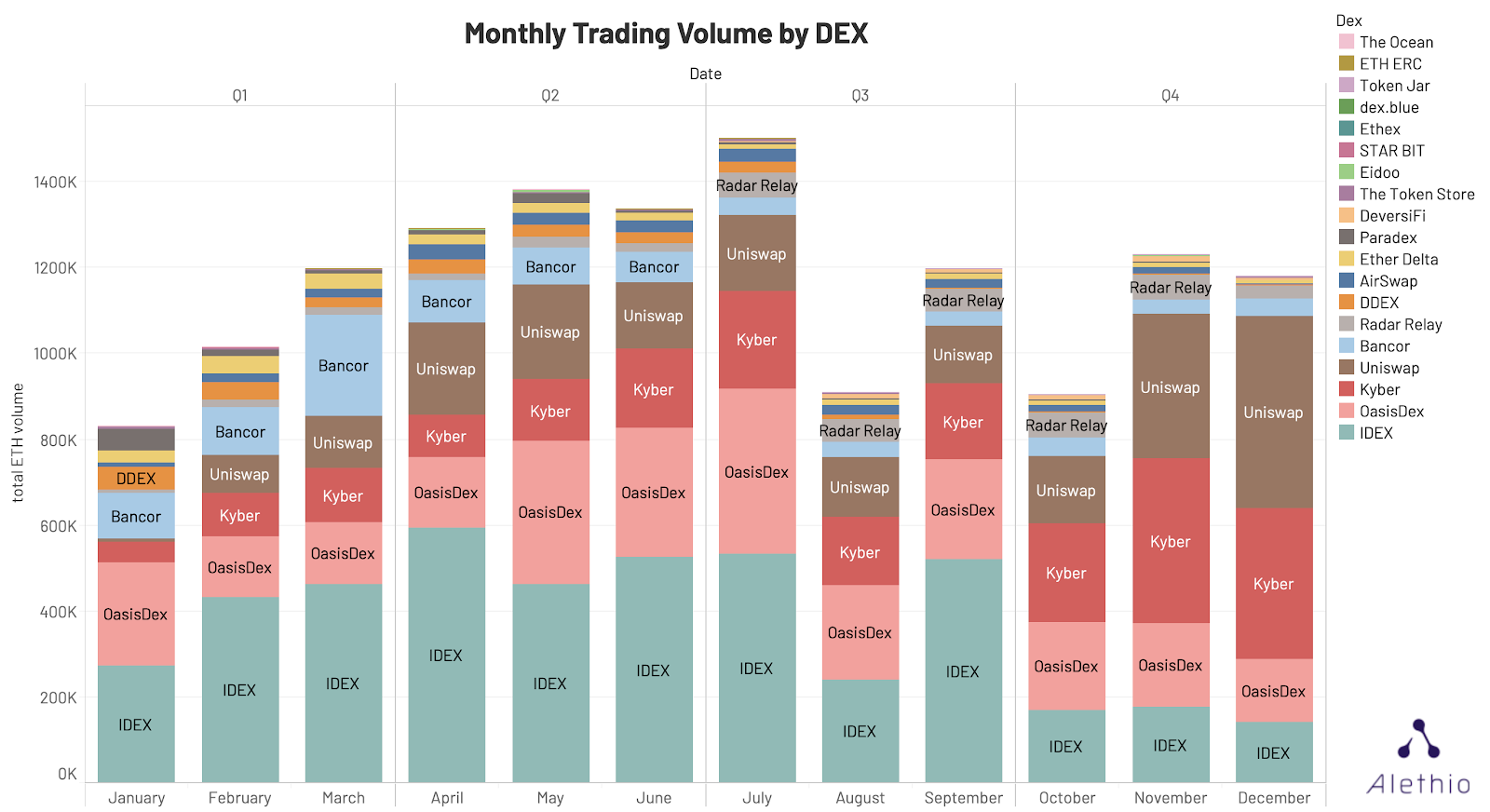

Source: Alethio

In 2020, order book-based DEXs like IDEX, Kyber, or 0X have been eclipsed by protocols using AMMs. It was exactly the innovative feature of automated market making that helped Uniswap dominate on the DEX throne in 2020. Its rise encouraged an explosion of innovation in AMMs. Uniswap’s descendents such as Curve or Balancer introduced AMMs with different flavors of pricing functions. One of the reasons AMM-based exchanges prevailed over order book model relates to their cost-effectiveness in terms of gas fees. This might be however just temporary and may change as layer two solutions become more widespread in the ecosystem.The wave of craziness caused by yield farming and exponential rise of DeFi in Q2 of 2020 meant also a dramatic growth of decentralized exchanges in all aspects. DEX trading volume started to match the one of centralized exchanges, and their value proposition increased as a number of different applications have been sourcing liquidity from them. User interface has dramatically improved on many fronts too especially with aggregators such as Matcha or 1inch.exchange that split order and route them through different protocols to avoid high slippage. Exchanges such as Loopring made successful debuts in implementing layer two architecture, more precisely zkRollups, within the DEX realm which should help to relieve the burden of DeFi users in the form of exorbitant gas fees that have been almost prohibitive for some applications.

Lending platforms

Lending protocols have been the major use case for DeFi from its early days. Their unique value proposition offers trustless lending of crypto assets via smart contracts. The pivotal project that spearheaded trustless lending was MakerDAO. Its founder, Rune Christensen started to work on it in 2015 and by 2017 the MakerDAO Foundation sold a good chunk of its MKR tokens to some serious VCs such as Polychain Capital and Andreessen Horowitz. MakerDAO gave the DeFi space one of its core building blocks in the form of Dai — a stable coin pegged to the value of a dollar. Dai is minted by a smart contract when users commit collateral in the form of ether (or some other coins). The minimal value of the collateral must be 150% of the amount minted in Dai. This mechanism essentially allows users to borrow Dai against their ethers. MakerDAO.The stability of MakerDAO is maintained via dynamic system of collateralized debt positions (CDPs), autonomous feedback and system of incentives. As MakerDAO deploys a dual token systen where its second token — MKR — functions as a governance token that allows its holders to decide which assets will be used as collateral for CDPs or what will be the costs of borrowing Dai.

In late 2019, MakerDAO introduced an important upgrade to its protocol — Multi-Collateral Dai (MCD) system — that allowed users to use additional assets as collateral for CDPs. While part of the community welcomed this step towards broader adoption and perceived it positively, many voices raised their concerns about centralized nature of the assets being used as collateral, and its implications on censorship resistance of MakerDAO. MakerDAO had been for long the most dominant project in the space and its readiness has been tested multiple times.

The most challenging moment occurred during the sell-off on March 12th 2020 — also dubbed as "Black Thursday". The huge panic at the world’s stock markets caused by uncertainty spreading alongside with Covid-19 did not avoid crypto either. The massive sell-off in crypto triggered unintended consequences for the MakerDAO ecosystem. The rapidly plummeting price induced congestion of the Ethereum network as demand to transact skyrocketed. As gas prices reached unseen heights price oracles failed to update their feeds which caused lagging in the process of CDP liquidation. Once the oracles caught up and got updated they triggered CDP liquidations en masse. The MakerDAO system has been designed to cope with such a situation by auctioning off the collateral in CDPs. The capital raised in the auction is used to pay back the CDP debt. However, because of congestion of the network and subsequent delays in oracle updates, some liquidators were able to win the auction with bids of zero Dai, and essentially buy Ether worth $8 million for free.

This resulted in a situation where over $4,5 million worth of Dai was left unbacked by any collateral, CDP owners lost millions and the whole MakerDAO system was undercollateralized. The system is designed to deal with a protocol debt with re-collateralization via auction of newly minted MKR tokens. The amount of MKR tokens minted during re-collateralization after the Black Thursday exceeded the amount of tokens burnt since the launch of MakerDAO. The aftermath of the event brought also a class-action lawsuit against the Maker Foundation and associated parties for alleged intentional misrepresentation of the risks associated with CDP ownership. Apart form that, the dilution of MKR tokens supply, and changes in some of the protocol parameters MakerDAO survived one of the most crucial moments in its history quite well and soon after it became the first DeFi project that managed to locked on its protocol more than a billion dollars.

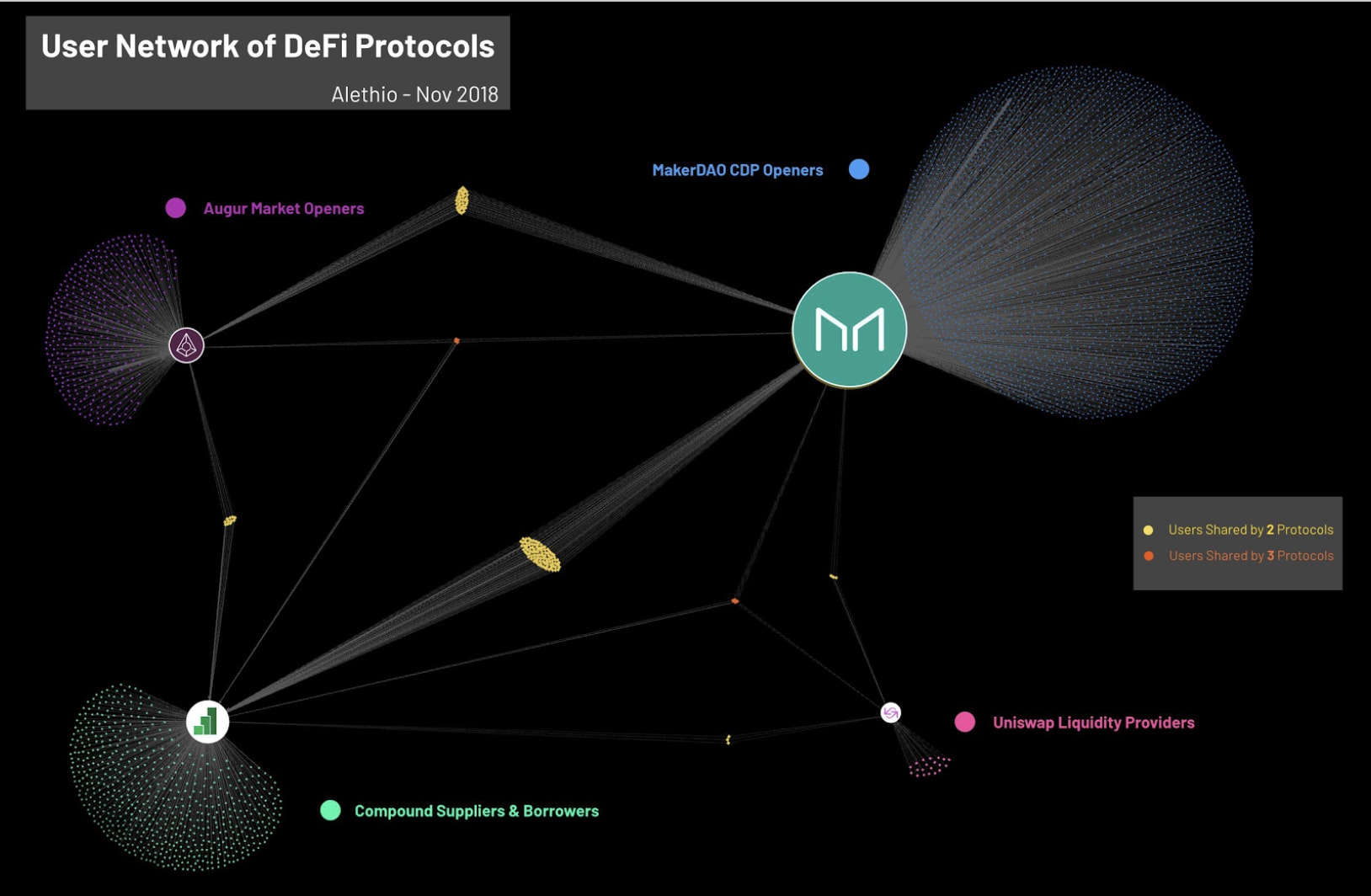

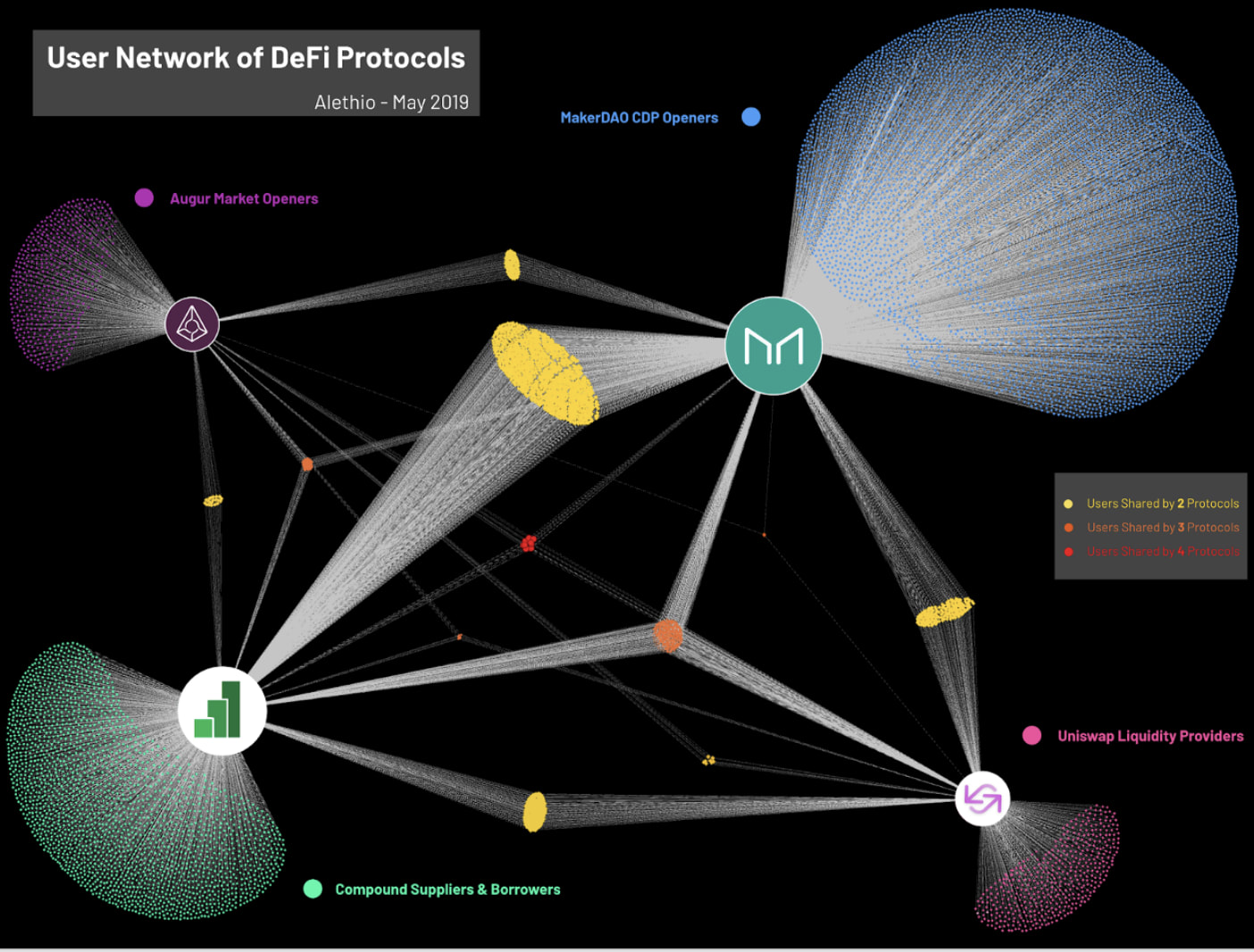

Source: Alethio

While MakerDAO allowed users to borrow Dai against their ETH collateral, the first project that let the users to lend and borrow ethers and Ethereum-based tokens was ETHLend launched in 2017. It rebranded to Aave in January 2020, and soon afterward it even took the DeFi throne from MakerDAO. Aave later on pivoted another interesting feature in the space — credit delegation a.k.a undercollateralized loans. Unsecured loans common in traditional banking had been unheard of in early days of DeFi. Aave achieved this via allowing depositors with unused borrowing power to delegate a credit line someone whom they trust. By doing so depositors can earn some extra interest rate. The closest competition to Aave, Compound, initially launched in September 2018 and managed to operate in a tokenless fashion for quite some time before it triggered the yield farming craziness with introduction of COMP governance token.Other lending platforms include Dharma, dYdX, InstaDapp, bZx and others. Each of them differs in minor aspects and parameters. While Darma takes pride in simplifying interaction with DeFi protocols via smooth UX, dYdX and bZx target more experienced and sophisticated traders with advanced trading tools.

One subcategory of loans that emerged and got under scrutiny in 2020 were flash loans. This type of loans allows anyone to borrow ethers (or other assets) without any collateral. The catch here is that flash loans need to be repaid in a single transaction. They are atomic and therefore do not represent any risk for the lenders. If they are not repaid at the end of a transaction the whole transaction cancels out, and thus doesn’t happen.At first glance this concept may be difficult to grasp or find useful compared to regular loans we know from DeFi protocols or traditional banking system. The composable lego-like structure of DeFi space does indeed provide use-cases where flash loans may be useful. The concept got introduced in 2018 by Marble protocol but it became more widespread with the launch of Aave and dYdX in early 2020. Flash loans have been the center of attention mainly because a number of “hacks” that capitalize on them. The first major hacks occurred in February 2020 when penniless attacker instantaneously borrowed hundreds of thousands of dollars of ETH which he deployed in other on-chain protocols while siphoning off another hundreds of thousands of dollars in stolen assets just to pay back the loan in the next line of the transaction’s code. All this in a single transaction.

The bZx Attack reconstruction:Attacker borrows 7500 ETH on iETH using flashBorrowToken()Attacker converts 900 ETH for 155,994 sUSD on Kyber.Attacker converts 3518 ETH for 943,837 sUSD using Synthetix’s exchangeEtherForSynths()Price 0.0037 sUSD/ETH (sane rate)Attacker borrows 6796 ETH on bZx, sending 1,099,841 sUSDPrice 0.006 sUSD/ETH (distorted rate)Attacker transfers back 7500 ETH to repay the loan.Attacker gets a profit of 2378 ETH.

Source: Alethio

Flash loans are indeed a very interesting economic concept that is own solely to the blockchain realm. This kind of arbitrage is not the only use case for them, though. They can significantly ease the interaction with DeFi protocols, especially when it comes to sophisticated transactions. As Stani Kulechov, the founder of Aave, pointed out in our discussion:

And what you now basically can do is you can swap your collateral in the MakerDAO system. For example, you borrow a flash loan, in Dai, and you close that CDP. And you sell BAT in Kyber or Uniswap for ETH, and then you open ETH-based collateral to mint Dai and return the Dai back to Aave. The magic is that everything happens in one transaction here.You could actually even create multiple functionalities as you can even add here a currency swap and interest rate swap. So instead of changing just the collateral, you could change the position from, let's say, from MakerDAO to Compound, and also if there's a cheaper loan on (USDC) than (Dai), you can also swap the currency into USDC. And you could even automate this thing so it is done for you once a week. And everything will be using flash loans and these transactions.

Unlike traditional loans, flash loans do not constitute any of the risks commonly present in lending. Lenders do not bear illiquidity risk, neither default risk nor they bear opportunity costs of the capital they are lending. Given this, it is reasonable to assume that costs of loans will race towards zero fees in the future.On the other hand, they may represent significant security risks for the ecosystem. They give huge chunks of capital at disposal to whoever asks for it. In such a sophisticated, complex and dynamically changing environment such as DeFi there is no doubt that we will see more attacks utilizing flash loans to exploit vulnerable protocols. Also, it is not hard to imagine miners getting rogue to compete in efforts to steal the blocks for themselves. The incentives to do so might be quite high. The upcoming sharding architecture of Ethereum 2.0 might too bring unforeseen changes into the lending landscape as we know it today.

Source: Alethio

Risks of Lending Protocols

Lending protocols are the main driving forces in DeFi. In August 2020, over 70% of all ETH used in DeFi was distributed across Maker, Aave, and Compound. It is worth to lay out three main risks that lending protocols entail.Technical risk is probably the most significant one not only in lending but in DeFi or any smart contract applications for that matter. It represents the risk of the smart contracts not behaving as intended. While it is a common practice with most of the high profile platforms to undergo security audits which significantly reduce this type of risk we can not eliminate it completely.Other risks involved relate to external factors such oracles or contract administrators (if there are any). Oracles may be manipulated into providing malicious data (and say breaking the dollar peg), and administrators may change system parameters. Worth to note that, some platforms, like Uniswap, have no external risks, and therefore are in general safer to use.Economic incentives, or failure of thereof represents another risk category. DeFi applications are rather complex codebases placed out there on the nasty high grounds of the internet. Each application alone may constitute incentives failure risks, not to mention interaction of hundreds of such interconnected applications. As with other risks, some protocols are vulnerable more and some less. Needles to say that DeFi as such as one huge economic and technological experiment that is conducted straight away in the production environment, for those bold enough to touch it, it may bring sweet gains as well as painful losses.

Derivatives

Derivatives are another category of products with significant presence in the space of decentralized finance. Derivatives and synthetic assets (synths) allow users to gain exposure to assets without having to purchase them directly. Like in traditional finance, in DeFi too this is desirable mainly in order to reduce volatility and increase liquidity of the assets.While the first synthetic asset to garner adoption was Dai — an asset with a soft-peg to the US dollar — in this part we focus on protocols that have been specifically designed to create synthetic assets. The main value proposition of such assets is that they can provide leverage and exposure to any asset as long as there are reliable price feeds available. The key benefits of such instruments in DeFi include financial inclusion, composability, and the option to create unique and exotic assets.Synthetix has been the most popular protocol in this category with over $650 million of total value locked (TVL) at the time of writing. Some of its competitors include the UMA protocol or the MARKET protocol. While they do share certain design traits such as they all operate on Ethereum or mint synthetic assets against some level of collateral, they differ in differ in some more technical details.In Synthetix, users minting assets, say sUSD, take position in a debt pool. This debt pool is backed by SNX tokens staked by minters. This means that while minters’ debt remains fixed in respect to the proportion which they are responsible to repay, the value of this debt changes over time. Therefore, all synthetic tokens are issued against a single aggregated collateral pool of SNX tokens.The UMA protocol, on the other hand, silos the collateral per each synthetic asset separately. The mechanics behind UMA protocol differs in using structure similar to a total return swap, commonly used in traditional finance. Therefore, synths created through UMA have expiration date while those on Synthetix are perpetual.Moreover, UMA synths always require a counter-party that takes the other side of the swap while in Synthetix this role is taken automatically by the SNX stakers. A notable design feature pioneered by UMA are so called “priceless contracts”. What it boils down to is essentially replacing price oracles with a crypto-economic game incentives to make sure traders and liquidators don’t lie about the price of the assets.Unlike Synthetix, UMA and MARKET both use Dai as collateral for their synths. The MARKET protocol functions similar to UMA except of a few differences such as it does not require overcollateralization.

Note that in addition to the above-mentioned derivate protocols there has been an ongoing trend of new derivative trading platforms such as dYdX, Serum, or MCDEX that allow trading perpetual contracts. All the above-mentioned projects implement perpetual swaps on a Central Limit Order Book (CLOB) where traders deposit collateral into a smart contract, liquidity providers post limit orders on the CLOB, and takers cross the spread. While this model offers a rather simple and elegant solution with efficient capital allocation, tight spreads, and lots of leverage, it does make bootstrapping liquidity difficult, and requires insurance fund and reliance on external oracles to determine the funding rate.

An alternative to this particular design of perpetual swaps is found in implementing perpetuals swaps on a Virtual Automated Market Maker (vAMM). In this model, there are no makers as everyone is a taker trading assets up and down the bonding curve that quotes prices to the users according to pre-defined rule set. This model does similar design trade offs, but unlike CLOBs, it does guarantees liquidity, and therefore it is easier to bootstrap.Further derivates and synthetic instruments could include other platforms that allow decentralized prediction markets of which the most popular are Augur, Gnosis, Erasure and some others. All of these allow to speculate on the outcome of a future event, most commonly in the form of binary options (e.g. Will Putin still be a president by December 31st, 2021?). These platforms are optimized for betting on events like politics or sports or things that are difficult to bet on. Such predictions rely on external oracles, and due to their nature they hardly attract liquidity. Nonetheless, prediction markets are integral and growing suite of DeFi protocols.

Insurance

A special category of derivatives in DeFi is made up of insurance protocols that allow protect not only DeFi investors against losses. The rate at which cryptocurrencies have been growing outpaces the growth and maturity of the underlying infrastructure. Therefore, as in traditional finance, in DeFi too, protection, insurance, and hedging tools are essential to foster continuous growth of the space. Even though DeFi protocols to large extent aim to be built on trust-minimizing and open-source technologies, the major events of the past such as DAO hack or Parity’s multisig are too vivid in the memories of progressive and often too risk-averse crypto investors. Taking into account that smart contract applications are in general riskier than conventional apps, let alone the fact they operate billions of dollars and are intertwined in the wild open internet, there are very good reasons to have protection mechanisms in place in order to mitigate all kinds of risks.

A lot of risks found in the crypto space is impossible to be covered by traditional insurance industry, and thus decentralized insurance protocols are necessary to evolve. In its essence, insurance is about coordinating financial flows of group of stakeholders. This is something that can be done by smart contracts quite well in an automated fashion, and without reliance on (expensive) middlemen.Etherisc has been the first project to make waves in the area of decentralized insurance which launched in 2016. The protocol features its native DIP token and its distinctive feature, compared to other insurance protocols in the space, is that it uses parametric insurance, and thus can cover against (catastrophic) natural events. Etherisc pivoted initially with a flight delay app that allowed anyone to get insured against their delayed flights. In 2019, it launched along with Aon and Oxfam the first blockchain-based agricultural insurance for small farmers in Sri Lanka.Nexus Mutual pivoted the concept of coverage for smart contracts in May 2019. The protocols offers coverage for a failure some of the major smart contract applications in DeFi such as Compound, Uniswap, dYdX and others. The users choose which contract they want to cover, enter the length and the amount they would like to be covered for (in ETH or Dai), and subsequently they are provided with a quote based on various factors including the age of the contract since deployment, the complexity of its source code and more. If the user is happy with the quote, she just submits required amount of ETH into the capital pool, and receive NXM tokens in return which are later on used during the claims assessment process. The tokens, therefore, essentially represent a claim to the mutual’s capital pool.Apart from claims, these tokens are also used for governance and risk assessment too. The tokens operate on a bonding curve that sets their price. During the first year of the protocol’s operation the majority of the claims related to just two contracts: bZx and MakerDao. The capital pool size grew to be worth millions of dollars, and will likely grow in the future.Opyn is another major alternative for decentralized insurance which launched in early 2020. It is built on the protocol called Convexity was designed to provide generalized options on top of Ethereum. Opyn took the underlying protocol and created an interface that allows users to create put and call options. Interestingly enough, Opyn provides protection against both technical and financial risks. Opyn users who supply ETH collateral mint oTokens. These can be either added to the Uniswap pools to earn transaction fees or sold to insurance buyers. Unlike NExus Mutual, Opyn allows users to get insurance without the necessity to undergo the KYC process.There are a couple of others projects focused on providing insurance that are being built at the time of writing, and that have potential to be useful once they are in production. These include Hegic, Unslashed or SmartPiggies and some others.

The vast majority of these projects live on the Ethereum network, with minor exceptions that operate on other networks like Solana, EOS or Cosmos. We’re likely to see DeFi applications spilling over to other blockchains too, though, their composability is questionable. The first derivative attempts occured also on top of Bitcoin’s Lightning Network in the form of LN Markets that launched first CFDs in spring of 2020.Overall, there are multiple variables in which synthetic protocols differ — from conceptual design differences such order book vs. AMMs, on-chain vs off-chain components, through collateralization ratios, types of collateral, to aggressiveness of liquidations, the degree of reliance on oracles and much more. The right combination of the above-mentioned ingredients is yet to be discovered, and the road to that discovery is paved by plentiful experiments, some of which will turn painful for the its participants.

Stablecoins

Volatility of cryptocurrencies has been for many people a single reason to not usem. Cryptocurrencies have been indeed very volatile mainly because of the nascent stage they are still in. We may expect this to continue to be the case unless they reach new heights in the market capitalization — at least an order of magnitude higher. If cryptocurrencies were designed to bank the unbanked they have been failing to do so mainly because of their volatile nature, which is a risk many of the unbanked can’t afford.However, stablecoins are not valuable only for the unbanked, but for the vast majority of traders too as they allow to protect their fortunes. The ability to transact a price-stable asset on the blockchain has been the holy grail for many crypto enthusiasts. Current frequent use cases for stablecoins include: commercial cross-border payments, remittances, recurring payments, long-term loans, and trading and wealth management.Of course, the concept of stability is very relative in the dynamic world we live in. While the major fiat currencies such as euro, dollar, or yuan are considered to be stable, this assessment always depends on the time scale and referenced value we use to compare their stability. As such, stability does not exist, but most of the people like the illusion of it too much to give up on it. In this part we explore how the landscape of so called stablecoins evolved over time and how they differ in their design choices.

In general we recognize four main categories of stablecoins:1. Fiat-collateralized — e.g. Libra or Tether2. Commodity-collateralized — e.g. Digix Gold or PaxGold3. Crypto-collateralized — e.g. Dai or sUSD4. Non-collateralized also known as algorithmic — e.g. NuBits, Basis

The first stablecoin in the history fof cryptocurrencies — BitUSD — was issued in July 2014. It was issued on the BitShares blockchain, and it was the brainchild of two legendary personas of this space — Dan Larimer and Charles Hoskinson. BitUSD was backed by BTS which was the native token of the BitShares blockchain. In 2018, the coin’s peg to USD got broken and from that point onward its value has been floating around 80 cents per 1 BitUSD. Another stablecoin that emerged soon after the first one in 2014 was NuBits. NuBits pivoted the idea of non-collateralized stablecoins based on the concept of Seignorage Shares that was introduced in a paper by Robert Sams in the same year. The coin suffered a couple of serious crashes during its existence, and ultimately lost 94% of its value.

In the late 2014, after the two innovative approaches to stablecoin design launched, a third coin with rather traditional approach was introduced — Tether, or USDT. Tether is issued by the Bitfinex exchange, and has been very controversial for most of its existence. This is mainly because of the $31 million hack, price manipulation claims and lack of financial audit. There are rumours that entities behind Tether played a vital role in Bitcoin 2017 bull run by artificially driving up the price. Tether has also switched banks several times over the past years, and had rathe problematic relationship with its auditors and the US regulators. Uncertainty over Tether’s reserves got reflected in the form of a couple price dips, but the coin was able to sustain its peg to the US dollar for most of the time.Despite this, Tether remains the most well-known stable asset in the cryptocurrency market. The coin was initially issued on the Omni protocol that operates on top of Bitcoin, but by mid 2020 operates on eight different blockchains including Ethereum, EOS, Algorand, Solana, Tron, Bitcoin Cash, and Liquid Network with the market cap reaching almost $70 billion. It also became the most used ERC20 token.

A few billion short of Tether’s market capitalization there is another major version of a crypto dollar — USD Coin, or USDC. USDC is managed by a consortium called Centre that consists of regulated companies like Circle and Coinbase. Since its launch in September 2018, USDC has been growing fast in adoption and two years later its market cap crossed the $2 billion mark. While operating mostly on Ethereum, the coin got introduced to Algorand, Solana and other chains as well. As the market with stablecoins has seen explosive growth in the past two years, driven mainly by DeFi, there are increasingly more companies introducing blockchain versions of fiat money. Other major fiat-collateralized crypto dollars include Paxos (PAX), TrueUSD (TUSD), or Gemini Dollar (GUSD).

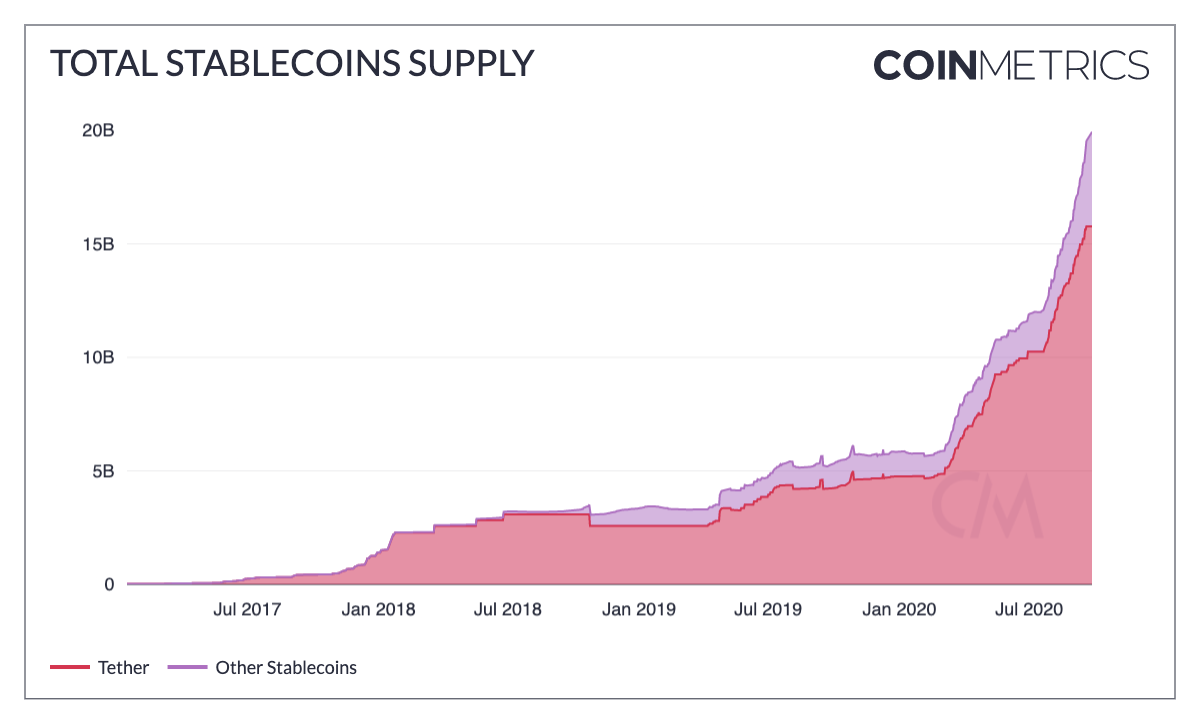

Source: CoinMetrics

Amongst the fiat-collateralized stablecoins there is one that stands out and triggered a great deal of discussion not only int he crypto community but in the regulators’ circles globally. Libra managed to do this far ahead of its launch. The grand project spearheaded by Facebook, and dozens of other high-profile companies such as Spotify, Paypal, Uber, Vodafone or Mastercard that joined the consortium, was announced in June 2019. The announcement caused a lots of concerns amongst the regulators that were already worried about Facebook’s practice when it comes to protecting users’ data. Leting the giant handle payments for its more than 2 billion users could truly disrupt the status quo of the financial world. Even though the initial design of Libra operated with permissioned network, its paper suggested a transition towards permissionless network is considered for the future.Interestingly enough, Libra was supposed to be different compared to other stablecoins in that it was intended to be backed by a basket of currencies, rather than just a single currency. This would indeed represent a currency with new monetary quality which is not something central banks are happy to see. As the wave of (not only) the US government scrutiny hit the Zuckerberg’s team, the apologetic rhetorics when explaining innovation behind Libra was not enough to lull the regulators, and Libra had to remake many of its original plans while significantly reducing its potentia. The government pressure deterred also quite a few consortium members that decided to quit. To address the regulatory concerns, Libra created a massive compliant global platform, hired former banking executives, scrapped the vision of a future permissionless network as well as the concept of a single currency backed by the basket of currencies. Instead, Libra will issue merely another versions of fiat money on its network. Still, it may become a powerful network for the upcoming years that is likely to drive interest and adoption of digital currencies.

Commodity and Crypto-collateralized stablecoins

The same way a digital currency can be pegged to any national fiat currency, it can be pegged to a precious metal. This was the original idea of e-gold that we talked about in the second chapter. Given the popularity of e-gold in the early days of digital currencies it is quite surprising that gold-backed cryptocurrencies are not more widespread. One of the possible explanations is that post-Bitcoin era came with much distrust towards third party custodians that are required to store the gold reserves. Nonetheless, there were multiple attempts and initiatives to launch golden crypto even in the Bitcoin era. Many of them failed to get any meaningful traction. From all of them, the most prominent was Digix Dao that was founded in late 2014 and introduced Digix Gold Token ( DGX) backed by one gram of gold. It started to get more significant momentum during its crowdsale in 2016 but later on its star got eclipsed with the advancing ICO frenzy. By 2020, the major gold-backed token is Pax Gold, or PAXG, that is redeemable for an ounce of gold. The token is issued on Ethereum by Paxos, a regulated US-based company. One of the great advantages of digital coins backed by gold is that owners do not have to pay storage fees as it is common in conventional investment instruments offering gold. Instead, they can lend coins on some of the services supporting it, and earn interest rate. Interestingly enough, Tether has entered this arena too by issuing Tether Gold (XAUt) that is likewise backed by one troy ounce. The token operates on both Ethereum and Tron.

Crypto-collateralized stablecoins have become quite popular even though they can’t keep up with the proliferation of fiat-collateralized stablecoins. As mentioned earlier, this concept was pioneered in 2014 by BitShares’ BitUSD. The concept had been iterated many times by projects such as Havven, Alchemint, or Steem Dollars but most importantly by MakerDAO and its Dai.Dai has been one of the early unicorns of DeFi. Since its launch in December 2017, it has allowed users to deposit ethers into a smart contract, and thus create a collateralized debt position (CDP) through which they can mint Dai. Technically this process involves further operations such as creating “wrapped” ETH (WETH) and turning it into Pooled ETH (PETH). Wrapping ETH allows ETH to behave like any other ERC20 token, and pooling it means that it joins the pool of all the ethers that are locked up, and against which Dai tokens can be drawn (minted). In a nutshell, the process of minting Dai looks as follows:

1. Deposit ETH to Metamask2. Wrap ETH --> WETH (via Dai.makerdao.com)3.Exchange it for PETH (Pooled ETH) used for collateral4. Create a CDP (the loan)5. Lock your PETH collateral6. Mint new DAI (max. 60% of the collateral value)

Of course, there is a limit to which users can mint Dai against the collateral they provided. If they fail to maintain the 150% collateralization ratio, their position will be liquidated and penalized by penalty fee of 13%. Moreover, each “loan” taken incurs also a stability fee that is paid for upon repayment of borrowed Dai. The repayment is denominated in MKR tokens which are subsequently burnt.These risk parameters are subject to decisions made by MKR token holders that are in charge of governance and make up the MakerDAO. They also act as the last line of defense in case system-wide collateral value falls too low too fast. In unlikely events like this, more MKR tokens are minted and sold on the open market to raise more collateral, effectively diluting MKR holders. The Black Thursday in March 12, 2020 is an example of such an event. In the series of unfortunate events, the whole system had to be recapitalized by minting new MKR tokens in the amount bigger than the one burned during the whole existence of the project.Dai has been heavily used and integrated by all the major projects in DeFi. In one of the protocol’s most important upgrades, in November 2019, the number of assets accepted as collateral increased, and by the time of writing, users can mint Dai tokens against the spectrum of tokens such as BAT, WBTC, USDC, and more. In fact, the majority of the Dai’s collateral consists of USDC. The team behind the project has expressed plans to accept even more assets that could include real estates or other tokenized physical assets.This could increase the trust factor and the attack vector surface within the system, and thus make it more fragile, and potentially unstable for the future. Nevertheless, Dai has been one of the most sophisticated and advanced projects in the crypto space, that has a decent chance to succeed in the long term, even though it needs to be viewed as an ongoing experiment.

Non-collateralized Stablecoins with Elastic Supply Protocols

As we mentioned earlier NuBits was the first non-collateralized stablecoin to enter the crypto arena. Its failure did not discourage other teams to implement various designs in order to achieve what NuBits did not. While collateralized stablecoins have been largely dominating the space in the past years, the competing concept of “elastic supply protocols” has been recurring at regular rate. This family of protocols aims to produce non-volatile digital currencies that lack backing from any kind of collateral. They deploy various designs such as Seigniorage Shares to achieve this. The main idea is to have a currency with supply that algorithmically expands and contracts along with demand for the coin. In 2018, this idea was resurrected in the form of two protocols — Basis and Kowala. Unfortunately, a year later none of them was active anymore.

In 2019, the continuation came in the form of Ampleforth which introduced a “rebase function” that multiples or divides existing token supply by some value depending on the price divergence. For instance, if the market price of the token is 50 cents, diverging from the targeted peg of 1 dollar, its supply, and each holder’s wallet balance will reduce by the factor of 2. This happens gradually over a certain pre-defined period. In the case of Ampleforth it is 10 days. This mechanism has not been really working well in the first year of its launch, as the AMPL token experienced multiple long periods trading above, below and at its target price. While this can be justified by the nascency of the project, this mechanism is quite tricky as the downward spiral may cause disbelief in the minds of traders that are suppose to step in to converge the peg to its target. The mechanism alone may not be enough to motivate traders to partake in it. As Ampleforth is built on top of Ethereum, it enjoys not only the benefits of the network effect but also the drawbacks of its network congestion.

Unlike Ampleforth, other protocols with elastic supply such as Terra and Celo have built their stablecoins on brand new blockchains that are more suitable for everyday transactions, at least when it comes to the speed and costs of transactions. Their design differs in a few more aspects. Terra has multiple stablecoins pegged to different fiat currencies, and it utilizes a secondary token — Luna — along with a set of stakers to provide stability for the protocol. Luna functions as the reserve asset that is supposed to absorb Terra’s price volatility as the two can be always swapped at the hardcoded exchange rate. This ensures that Terra’s price volatility is reflected by Luna’s supply. Therefore, eventually the token supply changes algorithmically based on the nominal exchange rate, and thus relying on price oracles. In this seigniorage model, when the token is traded above the target price, the protocol makes “profit” by minting and selling its stablecoin in order to reach the price equilibrium. Inversely, if it trades below the minting profit is used to buyback the stablecoin. The whole mechanism is more complex as it needs to ensure that the reserve token, Luna, maintain its value too. This is partially achieved by incentivizing Luna stakers by transaction fees incurred by Terra transactions. Yet, a protocol like this may experience hiccups if the accumulated seigniorage for buybacks is not enough to reduce the token’s supply. Nonetheless, since its launch in 2019 stablecoins on Terra have exhibited stability.

A similar stability mechanism as in Terra can be found in Celo too. It utilizes a secondary token, Celo Gold, as a reserve asset absorbing the volatility of Celo Dollars, but unlike Terra it incorporates some reserves in addition to the dual-asset system. In the times of high demand for Celo Dollars, and thus the supply expansion, new Celo Dollars are minted and sold in exchange for Celo Gold. Acquired Celo Gold is deposited into the reserve, and diversified into other crypto assets. In times of the supply contraction, the protocol buys back and burns Celo Dollars using the reserve assets. Celo also deploys an on-chain constant-product market-maker, similar to Uniswap, as the price feed. Interestingly enough, Celo utilizes the EVM on their blockchain, and thus Ethereum-based smart contracts are easy to migrate to its network. For the future, this could be a good strategy to combine network effects of Ethereum while avoiding its scalability issue. While founded in 2017, Celo launched its network in early 2020.The pace of innovation in DeFi has been speeding up and many interesting concepts enter the stablecoins arena. These include e.g. RAI, launched by the Reflexer Labs, that intends to dampen the volatility of its collateral rather than aim at maintaining a specific peg, but at the time of writing it is too early to assess viability of their concept. Nonetheless, according to various sources by the end of summer 2020, globally, the number of operational stablecoins approaches one hundred, while similar number of projects are in development, with something over two dozens have been already closed. Out of those that have ceased their operation, most of them were backed by gold and some of them include even a high-profile projects such as Basis that managed to raise over $130 million from some of the most prominent investors in the space such as A16Z or Polychain Capital.

Interoperability

Assets

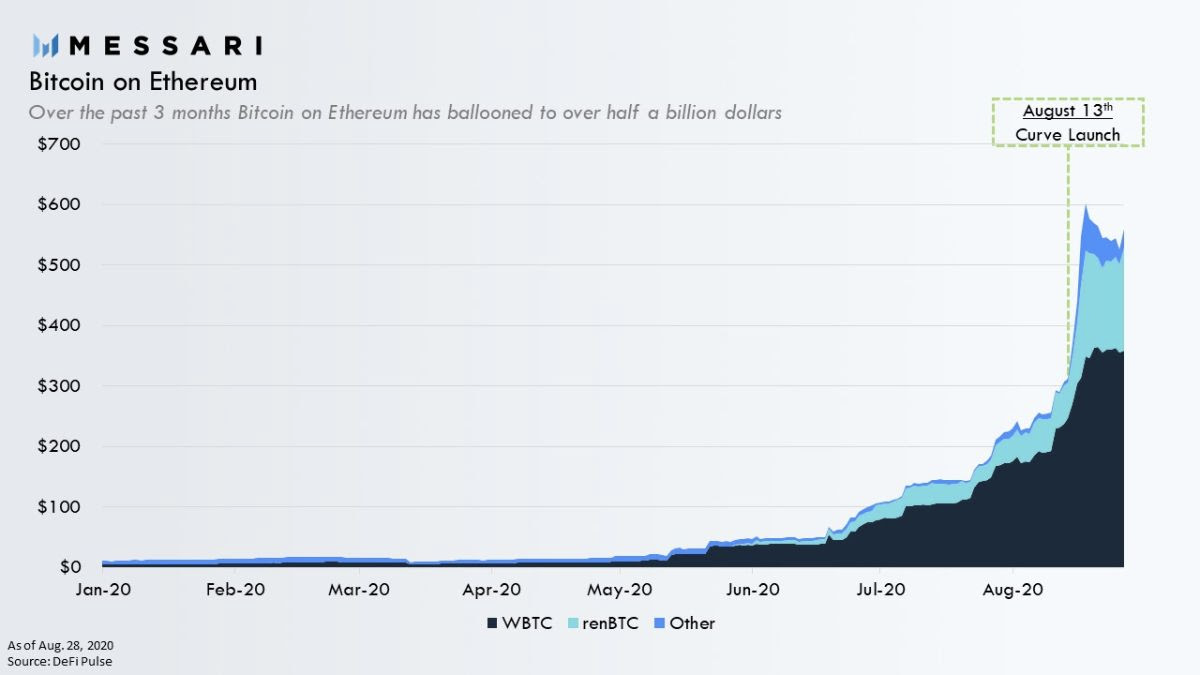

Interoperability has been one of the most researched and developed property in the blockchain space. As different protocols comes with different design trade-offs and properties, and decentralized applications occupy the whole spectrum of blockchain protocols, to capitalize on the potential of these protocols, it is crucial to ensure they can communicate amongst each other. Even though the majority of applications sticks together on Ethereum, at least for now, the scalability limitations may force dapps to spill over to other protocols. The ultimate interoperability in the blockchain realm will be achieved when all the major protocols will be bridged seamlessly, and their native tokens will be able to exist in all of them in the form of derivates.Such a state of things may happen in the future, but for the time being Ethereum has become the center of the decentralized financial universe, and thus most of the development efforts are focused on building bridges that would enable porting assets to and from Ethereum. The fruit of these efforts has been fully manifested in the second half of 2020 when over half a billion of exogenous assets, mainly tokenized bitcoins, poured into the Ethereum protocol. There have been multiple ways of bitcoin tokenization available. The number one way to do so has had the form of Wrapped BTC (WBTC). In this rather centralized solution, users entrust their bitcoins to the well-known and reputable custodian company BitGo. To dismay of many cryptocurrency aficcionados, doing so involves the KYC process.

Source: Messari

There are, however, other solutions that do not rely on a single trusted party. Out of these trustless protocols, the most popular has been RenVM. The nodes in the Ren blockchain fill the role of a decentralized custodian that locks up deposited bitcoins, and mints ERC-20 tokens — rBTC — on Ethereum. Naturally, they receive fees for their services. Anyone can operate the so-called Darknodes simply by bonding 100 000 REN tokens. RenVM ensures that these nodes are periodically shuffled into shards that utilize Ren’s secure multi-party computation algorithm to generate private key that is hidden to everyone and can not be used without cooperation of more than 1/3 of the Darknodes. RenVM supports also other assets but has been predominantly used to custody bitcoins.

Another decentralized alternative that recently hit the market, but was found buggy and had to relaunch is Keep Network. It features off-chain data containers dubbed “keeps” which are used to store and encrypt data via multi-party computation. Similarly to RenVM, node operators stake KEEP tokens, and may be slashed if they misbehave. The first application on the Keep Network was a trust-minimized bridge between Bitcoin and Ethereum that allows minting tBTC. Even though the solution utilizes complex and advanced cryptography its algorithms are considered more battle-tested, compared to the ones used by Ren which are yet to be open-sourced. Importantly, both protocols share a KYC-less approach to minting bitcoin-backed tokens.As Keep is more heavily backed by VCs, and thus its bootstrapping may be slightly reduced in comparison with Ren that held an ICO in 2018 and has much broader token distribution. Keep could represent a significant competitor for Ren or even WBTC for the future. A distinct feature of Keep is that in addition to staking Keep tokens it requires its node operators also to post 150% of the value of bitcoins in custody as collateral in ETH. Overcollateralization by two different assets makes it theoretically more resilient for the market hiccups and black swan events. While in 2020 still only less than a half percent of all bitcoins are tokenized on Ethereum, there is plenty of space to grow for all these projects.Over time it will be very interesting to follow development of the spectrum of various tokenized versions of Bitcoin, each of them with their own utility, scope of yield opportunities, and risk profile.

Protocols

DeFi has been slowly spreading to multiple blockchain protocols. The gravity of this trend has become more apparent in the light of Ethereum’s rising transaction fees that became insane for both users and developers deploying applications. Creating trustless and seamless bridges between Ethereum and other layer one protocols is of utmost importance for sustainability of DeFi. It is unlikely, though, that these protocols will be able to break the Ethereum’s community and developers moat. At the contrary, it is more likely that these layer one protocols will become effectively Ethereum’s layer two extensions.

One of such bridges is Wormhole. It is a bidirectional bridge between Ethereum and Solana that is built using Proof-of-Authority network consisting of so-called Guardians that are equally weighted in the network. Some of the major projects that started to build on Solana include Tether, Serum, or Terra. While Wormhole uses rather simplistic approach to network security and architecture with a multisig scheme, other protocols such as Thorchain deploy a Threshold Signature Scheme to handle transactions, which offers better privacy and cheaper transactions. This allows users to actually swap real assets for each other, and their pegged versions.

Unlike Ethereum, the Cosmos ecosystem does not rely on a single chain to facilitate data and asset transfers, but deploys various independent and application-specific chains that communicate through an interoperability standard, and utilizes a topology consisting of hubs and zones. Hubs route data through the network and connect different zones, and in that are similar to Internet Service Providers. Therefore, Cosmos provides developers with a pre-built framework with greater flexibility, compared to Ethereum. While such an architecture does not limit intra-zone composability, the independent nature of Cosmos zones may not be exactly smoothing when it comes to inter-chain composability. Nonetheless, the Cosmos ecosystem seems to provide a full-fledged alternative in DeFi as it has amassed projects that make up crucial building blocks. These include Band protocol (oracles), Kava (synthetic assets), Thorchain (AMM-based dececentralized exchange), or Terra (stablecoin) which is one of the most used blockchains in the industry, mainly due to the success of the payment app Chai that has been trending in Korea. The Q4 2020 launch of long-awaited Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol represents a significant milestones not only for Cosmos but for the whole blockchain space in general.Interestingly enough, Cosmos was able to gain approval even from some of die-hard Bitcoiners who are generally hostile towards DeFi or anything else that happened to be not related to Bitcoin. This is mainly because Cosmos introduced the concept of Peg Zones that allow to issues asset pegged to other blockchain assets, such as Bitcoin, and thus add them smart contract functionality. In these zones Bitcoin remains the native currency used for paying fees, unlike with popular WBTC where fees incurred are paid in ethers. This could negatively affect Bitcoin in the long term as its security may be undermined if transaction fees are absorbed by different blockchain.When discussing interoperability in blockchain, Polkadot, the brainchild of one of the Ethereum’s founders Gavin Wood, inevitably gets mentioned as well. Irritated by the slow decision making of the Ethereum community when it comes to sharding implementation, he decided to develop Polkadot not too long after Ethereum launched.Upon its launch in August 2020 Polkadot had immediately catapulted into the TOP 10 coins in terms of market capitalization. Similarly to Cosmos, Polkadot too connects multiple specialized blockchains — parachains — into one network. These are bridged into and secured by the main relay chain — Polkadot blockchain. Shortly after its launch dozens of DeFi projects emerged, including BTC Parachain that introduces trustlessly tokenized Bitcoin, or PolkaBTC. Polkadot’s design with limited slots for parachains gave birth to its sister network with lower barrier to entry — Kusama. During the fall of 2020 an interesting ecosystem started to form around these networks.

Bitcoin and DeFi

But Bitcoin’s relationship with DeFi is bidirectional indeed. Even though there is certain asymmetry in it as tokenized Bitcoin on Ethereum has been getting far more traction than DeFi projects on Bitcoin. The limited functionality of Bitcoin Script does not allow to bring full-fledged smart contracts onto the first layer of the most robust and decentralized cryptocurrency. Even though this can be partially enhanced through technological advancements such discreet log contracts, hash time locked contracts (HTLCSs), or stateless simple payment verification (SPV) that would allow cross-chain exchange between Bitcoin and Ethereum (including ERC20 tokens) and that is being worked by teams such as Summa and Arwen.DeFi on Bitcoin will be likely more driven from second layers though. In fact, this has always been truth since Tether got introduced on Bitcoin’s extension — Mastercoin (now Omni). Lightning Network pivoted already in the gaming industry through “Lightnite”, a battle royal shooter similar to Fortnite but with one important twist — players’ interaction trigger real-time monetary rewards or penalties, denominated in satoshis. In simple words, you can ean bitcoins by shooting players.The major DeFi driver on Bitcoin is another layer two project — the RSK protocol which operates as a federated sidechain to Bitcoin, and natively supports solidity smart contracts, and thus make it easy to deploy Ethereum’s dapps on it. Naturally, the entrée for any protocol that aspires to join decentralized finance are stablecoins. In the case of RSK this resulted in launching the Dollar on Chain (DOC) which is pegged to USD. More importantly though, in October 2020 RSK made waves by launching MakerDao’s Dai on its network via RSK-ETH bridge while signalling the network’s heyday is yet to come. At the same time an important piece of a puzzle was launched by the Hodl Hodl team that introduced a non-custodian and KYC-less Bitcoin-backed lending platform that leverages Bitcoin as collateral along with various stablecoins.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

The concept of Central Bank Digital Currencies , or CBDCs, may not belong into decentralized finance but it certainly may make finance more open. Even though for some they may embody the worst Cypherpunk nightmares as they may result in a seamless absolute surveillance machine. Due to their centralized and permissioned nature CBDCs are not considered to be cryptocurrencies. They merely adopt blockchain to enhance efficiency of the legacy financial system. Yet, these efforts may result users enjoying some new benefits such as increased transaction efficiency, asset programmability, and generally more seamless payment experience in retail and wholesale applications. Most CBDC concepts are built around a two-tier architecture that does not exclude commercial banks but where a central bank is a single issuer of a digital currency. Other financial institutions, banks, and non-bank service providers further function as licensed intermediaries that assist with life cycle processes.Early experiements in this space include projects such as the e-Krona done by Sweden’s central bank - Riksbank. The project was initiated in early 2017, and launched pilot in 2020. Similar timeline was followed also in the e-Peso project conducted in Uruguay and operated through state-owned telecommunication providers. E-Hryvnia has been successfully tested by the National Bank of Ukraine in 2018. Experiements with CBDCs have been done also in the Carribbeans as the Bahamian Central Bank rolls out project Sand Dollar by the ned of 2020. Th European Central Bank has been one of the first central banks to study digital assets with the release of the Vritual Currency Schemes report already back in 2012. Its CBDC taskforce was formed in 2016 and its activities have been conducted under the project Stella in joint efforts with the Bank of Japan. Similar endeavours are present also in Singapore via project Jasper, or in Thailand with the project Inthanon.In the past months, most of the attention has been focused on China that has been very vocal about their efforts to launch a Digital Currency Electronic Payment System soon. Development efforts behind digital Yuan may be setting up trends globally. Interestingly enough, new digital yuan may be resembling cryptocurrencies in many aspects. It will support chip-card wallets similar to traditional hardware wallets, and its architecture is supposed to leverage also public and private keys.Interestingly, some of the pilots explored proof-of-concepts with so called “anonymity vouchers” that allow for confidential transfers up to a certain limit. It is early to say what level of privacy will be possible with CBDCs but apparently some design patterns suggest that they may operate in networks where no single intermediary has a full overview of all the network activities at any given point in time, and the central bank only controls the current amount of currency in circulation.It will be interesting to see how these networks will be complemented by the privately-issued stablecoins, or how interoperable they will be amongst themselves. In a certain way, CBDCs may contribute to redesigning cash as a concept, and possibly create TCP/IP for money, even though this is more likely come from permissionless networks such as Bitcoin.There is a good chance that CBDCs will be quite interoperable given the fact that a few of them leverage protocols such as Hyperledger Fabric or R3’s Corda. These two frameworks might be the first movers in the CBDC space, but two recently launched platforms by Mastercard and giant Japanese messaging platform Line may be catching up soon.

Entering the 3rd Decade of the 21st Century

In 2020, decentralized and open finance has been the major driver of the whole smart contract space. It heated up markets to their hottest points since 2017. Even though it has not delivered the promise to democratize the finance quite yet as it has been predominantly occupied by whales and geeks. Nonetheless, it set Ethereum on track to settle over $1 trillion in transactional value in 2020 — approximately 10 - 20% more than Bitcoin. It gave a completely new meaning to the term “Gas crisis”, and created opportunity storm for so-called Ethereum killers to prove their are worth the hefty investments. We witnessed the monetary base of stablecoins to grow from $12 billion past $20 billion, only in Q3 of 2020. Liquidity mining sent DeFi usage as well as prices to new all-time high, and DEX volumes reached unheard of heights outperforming even major centralized exchanges.

True to its name, open finance will be driven by the fierce competition amongst the protocols that by default make their codebase open. The open-source culture results in a forking culture as well. Several archetypes of forks have emerged in the past months, and we will likely see more of them in the future. Most commonly, protocols are forked by fast followers that make merely a small tweaks in the original protocol just to capitalize on its popularity. Forks like Sushiswap, Kimchi, or Swerve have been the most notable examples of these. Of course, from time to time, protocols get forked in order to introduce crucial design changes and new functionalities. Some of the popular protocols got also their localized forks tailored for particular markets. Interface forks usually add new features and integrations that massively simplify interaction with protocols. These have been typical for aggregators, wallets, and dashboards. Cross-chain forks are increasingly more common as DeFi spills over to new blockchains. These are typically copycats of some successful dapps deployed onto new network. Last but not least, pump and dump forks are sadly often present wherever big money is. The curious task of DeFi users will be to navigate their way through these distractions in disguise.

Even though DeFi allows to eliminate financial intermediaries, and thus also some risks related to them. At the same time it introduces a new set of risks that will be mitigated by the growing maturity of the space, but at this time are quite significant. As billion dollar protocols emerge out of nowhere and attract capital through liquidity mining, assets allocation changes far more dynamic than in any other industry. This will pose a serious system design risk as especially nascent protocols are prone to be gamed, and to have buggy code. Moreover, even if the code operates as intended, the complex and sophisticated nature of dapps allows to exploit protocols through their mutual interaction. This in turn may result in liquidation risk, as many users already have found out. We have already discussed dangers related to oracle failures and on-chain congestion and this extensive combo of attack vectors may be amplified by the protocol-level risks related to transition to Proof-of-Stake, and introduction of sharding.The space will rise many challenges not only to financial, and technological world but the legal one as well. In some cases the legal accountability will be easier to attribute than in others. Protocols will be accessed both via dedicated interfaces and raw smart contract interactions. How legal implications will differ in either remains unclear for now. As Stani Kulechov wraps it up:

In terms of smart contracts and DeFi usage, I think they will follow, pretty much, this kind of browsewrap or clickwrap style agreements as a legal wrapper. So either you click to accept the terms or you accept them by browsing. There are quite extensive legal foundations on that in case law. But I think the new thing here is that you're now able to interact with smart contracts without front-ends and this raises a question of what terms will be applicable then.

DeFi will have to face many challenges itself. Providing confidential transactions in the environment of absolute transparency will be the major one. Counterintuitively, the “open” finance may not be detrimental to one’ s privacy. This will be a continuous and never-ending quest. But is is the one that is worth to take upon. Top traders and whales have been complaining about the surveillance of “degens” imposed on them by platforms like Nansen or Santiment that make it easy to watch wallets with significant holdings. For now, the privacy they seek is provided by centralized exchanges where blockchain transactions disguise in SQL entries. Soon it won’t be only casual passers-by that will be watching. The molochs in the form of intelligence and enforcement agencies will try to usurp this space — in the name of national interests.But countless of decentralized counter-measuers are rolled out to the market as these lines are being written. Some of them — Aztec, zk-Sync, or Stealth Swaps — are specific to Ethereum, others such as Nym, Findora, or Secret Network are platform-agnostic. While nowadays these protocols may be deemed useful only by the crypto burgeois, in the not so far future, they will be mostly protecting privacy and interests of regular people. They will be the building blocks of the utopian and freedom-aspiring hopes for a surveillance-free cyber space. The white to the CBDCs black. The Jedi to the Sith, if you will. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to educate about these technologies, to research them amply, to build them carefully, and to test them extensively. Their time is yet to come.